Since prehistoric times, art and ritual have served as foundational acts that articulate the collective memory of the species, and the connection between both symbolic fields has often been fulfilled through icons. Both in the photographic polyptych Street Icon (2013-2021), and in the intervention The Last Supper after Leonardo Da Vinci (2022), Vero Murphy revisits in the 21st century, the religious imagination that since ancient times made sacred icons a way of storing and transmitting mystical experience and narratives.

Derived from the Byzantine Greek eikōn, an icon is a painted or relief image in the Byzantine art process that Eastern Christians employed to demonstrate the sacredness of their representations and thus communicate a mode of spirituality. In his icon found on the street, Murphy documents this sort of «apparition» that consists of seeing the image of Christ ─by relationships of resemblance and associations connected to archetypes of the cultural unconscious─ as if it were naturally formed in the bark of a tree on a street in Joinville, Brazil.

The photographic documentation not only includes the portrait, from multiple angles, of the found image, at the instant it was perceived by the artist; but the periodic return ─her particular pilgrimage─ to the tree in which it appeared. Throughout the year, 2013, several Sundays and other days of the week, she portrayed this image that was gradually altering and that in the following years would be transformed to the point of being completely untied from its religious references.

The polyptych intersperses contemplative, purely iconic close-ups with street scenes that, by situating the image associated with Christ in the profane urban context, enrich it by incorporating the vision of Him into the daily flow of life. Apart from the act of choosing these images from the found icon and thus separating them to insert them into ritual and religious thought, the artwork is a dated chronological documentation, a record of a segment of tree bark nothing more. But in reality, also by the place of its appearance, Murphy establishes a filiation, as ancient as it is unconscious, with the sacred: as the historian Mircea Eliade asserted, with the discovery of agriculture, in whose domestication women played a decisive role, the plant kingdom became connected to religious representations.

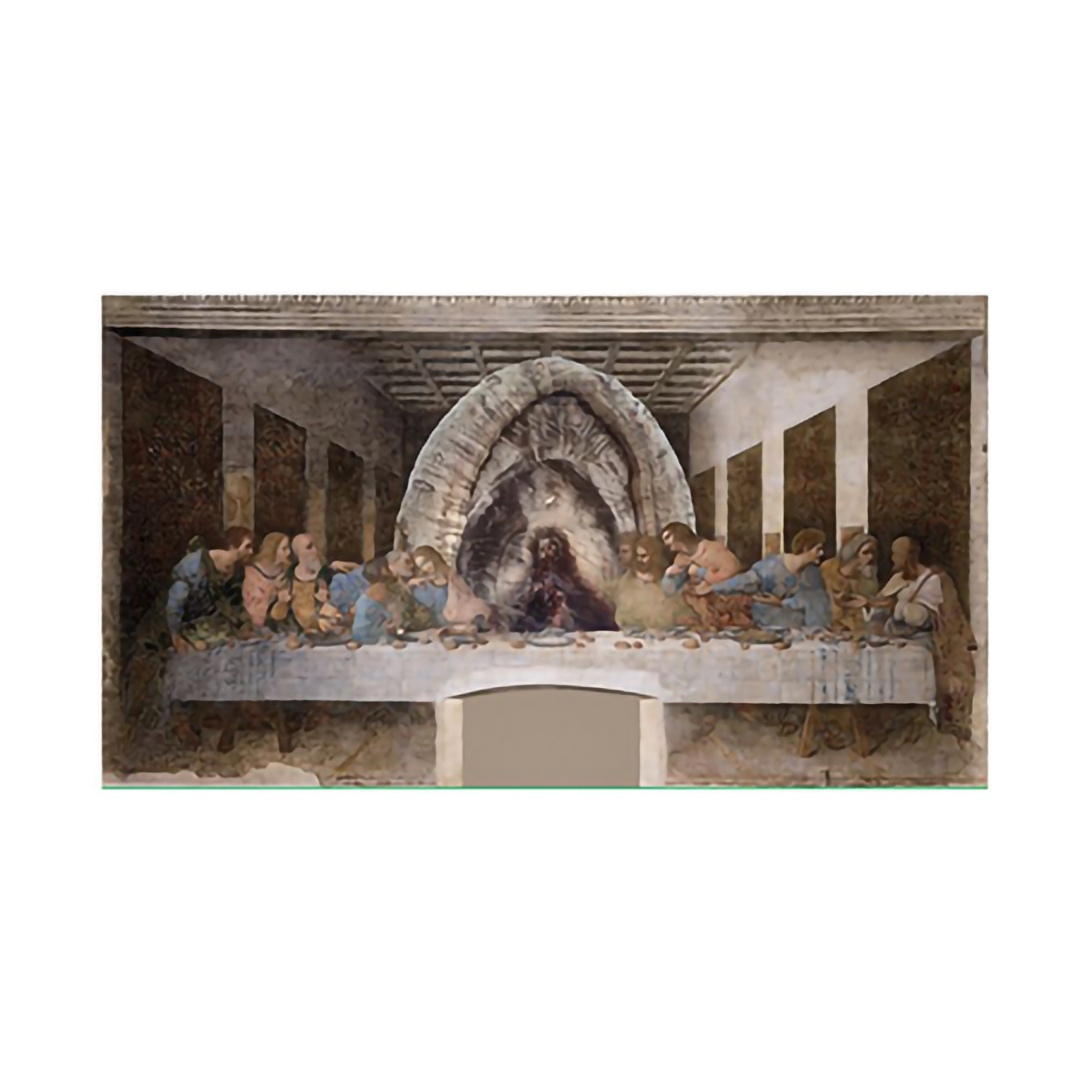

By inserting the icon found on the tree in the center of the scene reproduced from Da Vinci’s Last Supper, Murphy performs a way of replacing the iconography of Christ painted by the great Renaissance artist with the corrugated silhouette of «His» appearance on a tree in a random street in a region of Brazil. If the insertion can be disturbing, especially because the human features are diluted in the face made of vegetable fibers, it is precisely through this transition from the divine and anthropomorphic to the vegetable kingdom that the artist reminds us of the essential function of religion (from «re», to return, and «ligare», to unite): to rejoin the human being with the high and the low, with the celestial and the earthly, understood as the kingdom of all that was made in the timeless days of creation. Since the Council of Trent, in 1563, when the function of sacred images was reconfirmed, it was recalled that no image possessed «virtue or any divine attribute» and that its function resided in the mere aesthetic capacity to evoke in our mind the divine beings represented. The image on the trunk portrayed by Vero Murphy retains that function, but it derives it not from a human hand but from the very combination of the elements of nature ─water and wind, sun and wood─ in the simple skin of a portrayed tree. And this makes it even more singular.

Adriana Herrera.